Ueno Park Studies, Lecture 01

November 10th, 2017

Look from the Subject’s Perspective?

Grow an Extra Pair of Eyes!

Hidden Methodology of Art Research

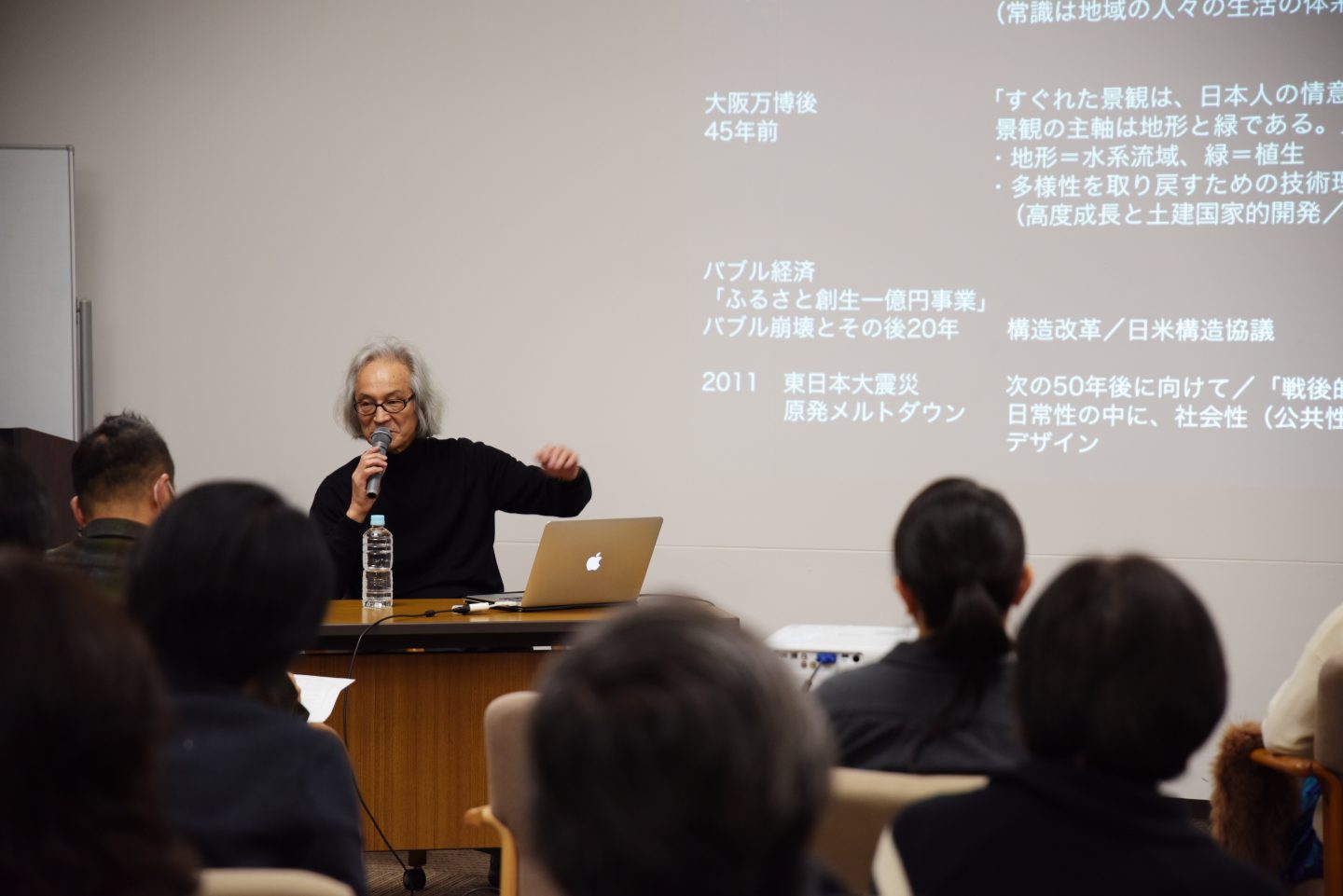

Photo by Keizo Kioku

Writer|Sayuri Kobayashi/Editor|Yoko Kawamura

Translation supervition and editing|Suzanne Mooney English translation|Ekaterina Dombinskaya

So what exactly is the research that artists do?

Photographer and art theorist Chihiro Minato hosted an Ueno Park Studies panel discussion with two guests – curator Fumihiko Sumitomo and the leading contemporary artist Tsuyoshi Ozawa.

One of the most recent works by Ozawa The Return of K.T.O focuses on a famous figure that is long gone from this world.

Ozawa traces his life through extensive fieldwork, and the result is history and fiction intertwined in one installation. The Return of K.T.O is a peek into Ozawa’s exciting research.

As a part of TOKYO Suki Fes 2017 where Sumitomo worked as a director, Ozawa supervised the Yanaka Art Project, which is a student exchangef project between Global Art Practice, Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts, and Beaux-Arts (de paris). The fruit that this project bore was “The Whole and The Part” exhibition. The premises where the works were installed were old Japanese traditional houses dating from the Meiji, Taisho and Showa periods that have survived to this day, and tell us stories of what life was like back in those days. One of the houses, the former Tani House, still had a lot of personal belongings of the previous owners when the project launched, so they had to start from cleaning it up. As Ozawa puts it, “I thought, you know, students would benefit from having access to a space that retains some of the traces of the people that lived there – visual, tactile, and olfactory… You encounter things you would never expect to see, and it can definitely lead to creative inspiration, or help gain a better understanding of how people back in the day used certain objects… “And regarding the degree of work involved in preparing the spaces he comments further that, When you do something like this it is almost an excessive amount of information and hints that come out.” He also points out, that students from Paris, who were used to European traditional houses made of rough and solid stone were puzzled by installing their works in Japanese houses of such delicate build. Minato suggests, that “if a Japanese student were to do a similar project in an apartment in Paris, there would be less chance of such misconception, because the Japanese city landscape is quite westernized, therefore, making it a familiar environment for a Japanese student.”

Sumitomo also shared his thoughts about the asymmetrical relation between the global and local which he encountered through hosting many artists from abroad in Japan: “I had an artist from Europe who brought to Japan work previously exhibited in a European art museum. And though the art museum in Japan where the work was to be installed was a white cube type space – exactly the same as it was when showing the work in Europe – the artist said, ‘I have a feeling this space is not as neutral as it should be.’ This artist was very aware of the peculiarities in shape and proportion of Japanese architectural structures. Europe has a long history behind the modern gallery space type known as the white cube, and Japanese architects are not always able to create from scratch the space that would comply with standards of the modern era of globalization.”

Additionally, Sumitomo mentioned how difficult it is at times for non-Japanese to understand Japanese art: “Using English – lingua franca of global communication – to describe Japanese arts can pose some challenges and unless the words are very carefully chosen in English they can end up misunderstood or misinterpreted. When big European and American museums have to deal with unfamiliar regions and cultures, they inevitably create books and catalogues about the subject in their local language, and attempt to raise the value of the works in that way. …(But) to understand everything is a fundamentally impossible task. Then could it not be true that by accepting the fact that there is a hard limit to how much we can learn and understand, we can enrich our worldview and provide an alternative means of perception? … This is especially so in Asia, distinguished by a lot of cultural and linguistic disconnection due to the island topography… So I think there could be a moment when the asymmetry between global and local… is overturned to form a relation opposite to what we see today.”

It could be argued that the first manifesto making an inquiry into the universal values of local Japanese communities and their relation to the process of westernization is The Book of Tea by Kakuzo Okakura (also known as Tenshin). Ozawa’s recent work The Return of K.T.O. displayed at Yokohama Triennale 2017 is a tribute to Okakura and shines a spotlight on Okakura’s journey to India. There, Okakura educated his disciples, including Taikan Yokoyama, who had substantial influence on Indian art and the emergence of the Morotai painting style. (TN: morotai is a style of Japanese painting, created by Taikan Yokoyama and his colleague Hishida Shunso). Ozawa recalls, “A temple where Okakura spent some of his time in India had a tributary of the Ganges river flowing at the back of the temple, that is why I thought, he must have taken a boat at least on some occasions, so I decided to take the boat too. The resulting experience exceeded my expectations for sure – that view from the boat in extreme humidity was like a revelation of morotai. I would not be surprised if not a single Japanese art historian is aware of this. … At that temple any visitor can get some curry free of charge, so I also thought to have some and reached for it with my hands, but it was way too hot and without thinking I yelped, ‘Ouch, that’s hot!’ in Japanese. Everyone around me laughed and I felt embarrassed, but you know, the chances are Okakura had exactly the same thing happen to him.” Such an approach of “looking from the subject’s perspective” allows one to understand the subject in depth. This could be a research method unique to artists.

Ozawa also points out that it is important to “have a local advisor”. He asserts, “It could be a local scholar, a curator or an artist – no hard rule. Someone who can understand the artist’s point of view but also has ample knowledge about the project and can provide a balanced opinion and an extra pair of eyes.” Minato, who often works abroad as a photographer, shares the opinion of the necessity of local help with Ozawa: “It must be fairly difficult to find a person like that. I think there needs to be some sort of system, a network in place to enable connecting people like that.”

This panel discussion was time well spent that helped to articulate the issues that resident artists in Ueno coming from abroad, as well as all artists, experience when delving into the realm of art research.

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of K.T.O., 2017 Photo by Sizune Shiigi

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of K.T.O., 2017 Photo by Sizune Shiigi

Photo by Akihide Saito

Photo by Akihide Saito

Tsuyoshi Ozawa

contemporary artist

Born in 1965, Ozawa graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts / Department of Painting / Oil Painting Major, and later completed postgraduate studies at Tokyo University of the Arts / Graduate School of Fine Arts / Mural Painting course. He is an associate professor at Tokyo University of the Arts / Graduate School of Fine Arts / Global Art Practice. Major works: “Jizoing” project – a collection of daily photos of a jizo in different environments (TN: jizo is a Japanese bodhisattva, one of the many incarnations of Buddha); “Nasubi Gallery” series of portable, miniature galleries made from milk boxes; “Vegetable Weapon” series portraying in photography young women holding weapons made out of vegetables; “The Return of …” series featuring well-known historical figures creating fictionalized version of their stories, and other works. Solo exhibitions include “Yes and No!” (Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2004); “The Invisible Runner Strides On” (Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima, 2009), “Imperfection : Parallel Art History” (Chiba City Art Museum, Chiba, 2018), among others.

Fumihiko Sumitomo

Curator

Born in 1971, Sumitomo graduated from The University of Tokyo / Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. He is Director at UENO Cultural Park, Director at TOKYO Suki Festival 2017, an associate professor at Tokyo University of Arts / Graduate School of Global Arts, Director of Arts Maebashi and was Co-curator at Aichi Triennale 2013 and Media City Seoul 2010 (Seoul Museum of Art).

He is a founding member of NPO Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT). Major exhibitions include “Possible Futures: Japanese Postwar Art and Technology” (ICC, Tokyo, 2005), “Tadashi Kawamata: Walkway” (Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, 2008), Festival for Arts and Social Technology Yokohama 2009, and other projects. He is the author of “Next Creator Book” and other works.

Chihiro Minato

photographer and art theorist

Born in 1960, Minato graduated from Waseda University, School of Political Science and Economics. He is currently Director of Art Bridge Institute, Professor at Tama Art University / Department of Information Design. He was Co-curator at Busan Biennale 2006, Commissioner of the Japanese Pavilion of The 52nd Venice Biennale 2007, Co-curator at Taipei Biennial 2012 and was the Artistic director of Aichi Triennale 2016. Major publications include “Of memory: the strength of creation and remembrance” (Kodansha Suntory Prize for Social Sciences and Humanities); “To the Cave: Archaelogy of the Mind and Image” (Serica Shobo); “Battle of Shadow Pictures” (Iwanami Shoten), and other works. Photo-books: “Our Mountains of Metamorphosis: morphogenesis and sacredness”, “Moji no Hahatachi – Le Voyage Typographique”, “In-between No.2: France and Greece” (EU-Japan Fest Committee) and other collections.