Ueno Park Studies, Lecture 03

January 23 rd, 2018

Are “Society” and Shakai Two Different Things?

How Reconsidering a Mistranslation Can Help to Make Better

Use of Public Parks

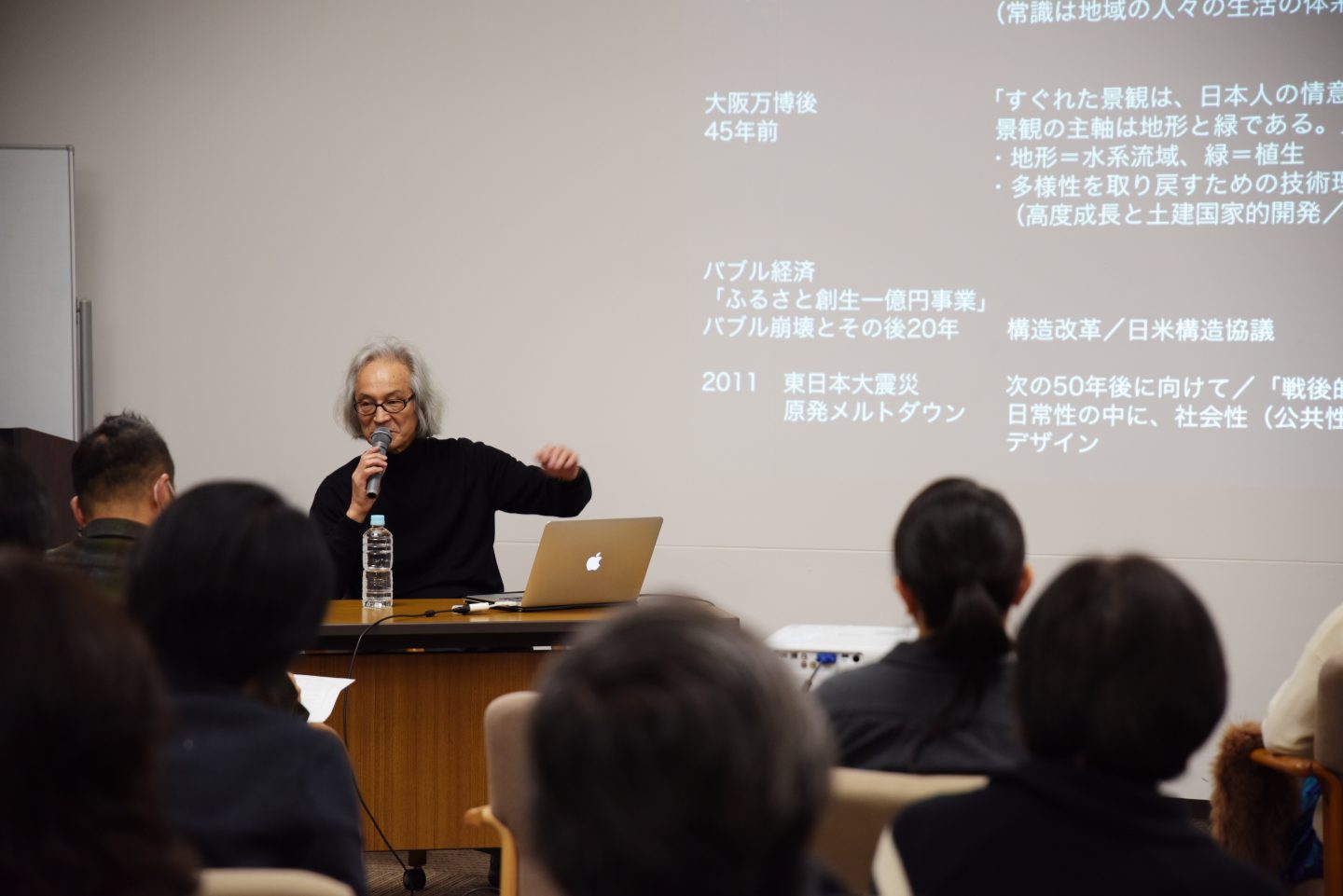

Photo by Akihide Saito

Writer|Sayuri Kobayashi/Editor|Yoko Kawamura

Translation supervition and editing|Suzanne Mooney English translation|Ekaterina Dombinskaya

As we contemplate the topic of public spaces and society as their underlying fundamental concept, we find ourselves trapped by the conceptual discrepancy born of mistranslations that took place as far back as the Meiji period. Historian Naoe Kimura invites us to solve the puzzle of these misconceptions in the context of Ueno Park – the first public park in Japan.

Society, freedom, equality, human rights, democracy… A lot of important concepts of modern-day Japan and our everyday lives were originally the words imported into Japanese from the languages and cultures of Western Europe during the second half of the 19th century. Our ancestors translated and shared the new concepts as one of the tools with which to build a new world in post-Edo Japan. Kimura focuses on language and concepts as means to research and analyze the modern history of Japan. She indicates, “Words and concepts help to give form to imagination, and determine what action we take towards the world around us, while the way those words and concepts have been accepted and realized is not universal throughout the world – there are a lot of ways to do that, largely influenced by local culture, geography and other factors surrounding the development of a community. Whether the concepts are accepted, misinterpreted or distorted along the way, or entirely rejected, the heritage of this process shapes the features and peculiarities of the plural moderns.” And, she continues further to reveal a shocking fact, “The word shakai was assigned to be a generally accepted translation of the word “society” during early Meiji period, but they do not mean the same thing. The word shakai has been used in Japanese language now for more than a century in a very particular way, and evolved into a unique concept.” For example, Kimura presents the word shakaijin (TN: literally, “society person”, used in Japanese exclusively in the meaning of “an adult with a full time job”) – a unique, established collocation in Japanese that has no equivalent in European language and culture.

The earliest encounter of Japanese with the English word “society” probably occurred at the end the 18th century, in the context of European studies and Dutch studies. At the time numerous variations were summoned in an attempt to best translate this word: majiwaru (to mingle), nakama (comradeship), nengoro (friendship), kumiai (union), shachu (staff or band) and many others. The Bakumatsu period (end of the Edo period) cross-culture travelers and scholars were already aware of the importance of finding the correct translation. Mamichi Tsuda and Amane Nishi, who were students dispatched to Holland during the late Edo period, translated the word “society” as aiseiyo-no-michi (lit. the path of coexistence), inferring that the core meaning of society was the mutual existence and mutual nurturing of people. Yukichi Fukuzawa, who visited America and Europe on many occasions as a member of delegations dispatched by the Japanese military government (bakufu), suggested that the equivalent to the word “society” in Japanese was jinkan-kousai (lit. fellowship of people), which puts emphasis on the interaction between the adult members of a large group, and the relationships within that group. Arinori Mori, a diplomat assigned to America around the same time period, insisted that the word “society” can not be translated into Japanese and should remain an imported loan-word transcribed using the Japanese alphabet ソサエチー (pronounced: so-sa-e-chi). Finally, after decades of struggling to interpret this word into something that would best reflect its true meaning, in 1875 the Japanese word 社会 (shakai) (TN: shakai consists of two characters, 社 – originally “shrine” and later any association of people, and 会 – gathering/meeting/club) was acknowledged as the most suitable translation. It is no coincidence that it was just a year before Japan’s first public park, Ueno Park, was opened to the public.

Similarly to the concept of society, public parks did not exist in Edo Japan until Shibusawa Eiichi, members of the Iwakura Mission, and other figures that visited Western Europe in the following years took note of European public parks. And finally in 1873 it was officially pronounced by the Japanese government that historical scenic spots renowned as such during the Edo period should be preserved and maintained as 公園(kouen) (TN: park. When written with Japanese, it is a combination of two characters, 公 – public, and 園 – garden, therefore literally “a public garden”. Ueno Park in Japanese is called Ueno Kouen), and the grounds of Kan’ei-ji temple (Ueno area) were named among them. (A Decree by the Grand Council of State No.16). In 1876, Ueno Park was opened and became the first public park in Japan. However, much later, in 1914, a Japanese Marxist economist Hajime Kawakami, in his essay “The Locked Door and The Paper Shoji”(1914) (TN: shoji is type of a paper sliding door in traditional Japanese interior) included in the book Looking Back at the Home Land – A Journey West, argues that the Europeans make the best use of public parks and public spaces because they consider a place like a public park “part of their dwelling, their home” and treat such concepts as the public park or society as integral parts of their everyday life. One can read between the lines that Kawakami sees the Japanese as a nation that is not very skillful in its use of public parks. Kimura concludes, “The common discovery for all these early explorers of foreign cultures was the fact that the people of the East and West think very differently about the establishment of human relationships and the core principles that define them. In other words, it can be argued that contemplation about shakai (society) and kouen (public park) leads us to the analysis of how the domain of “public” is formed, and how the people are expected to act while in that domain.” In fact, the period when these words were created coincides with the emergence of public spaces designed to be shared by a large amount of people. The same period is marked by the launch of public opinion oriented mass media such as newspapers, the opening of restaurants such as Seiyoken where the goal was to enjoy social interaction as much as food, and the establishment of theaters and the Japanese Diet. But in less than half a century the original purpose of public spaces faded away.

Given the context of all this, the translation of the concept “public” was not an easy task either. Ueno Park was created by a Japanese government decree as a kouen (public park), but there are records of that period that call Ueno Park kan-en (a government park). In Japanese, the characters 公 (kou) and 官 (kan) can both mean public or official, and are often used as synonyms, which leads to the confusion between the actual concepts of public and official. Kimura states that nowadays “The meaning of the character 公 (kou) includes the indication of being associated with administration, authority, or the ruling class. It is hard to completely disassociate this word from these attributed meanings. Despite that, 公 is a firmly established translation of the word ‘public’ which leads to confidence that its meaning is well understood by now, which is not necessarily true. Japan has extensive experience in interpretation of foreign languages – from ancient Chinese to modern European. When so much is imported and translated, distortions and misinterpretations are inevitable. And as the time passes and the imported word or phrase becomes widely used, we stop noticing the mismatch or distortion.” In this way, the so-called Galapagosization of concepts occurs – the creation of words and definitions that do not bear any meaning outside of Japan. Kimura declares, “We must be aware of traps and habits that we are prone to as Japanese language speakers, and take note that there is always a danger of distortion – deliberate or not – as a result of which a word can become something completely different compared to its original meaning. This way, by being aware of potential dangers, we can reconsider and reshape the ideas of a public park and society into something more universal and true to the nature of these things.”

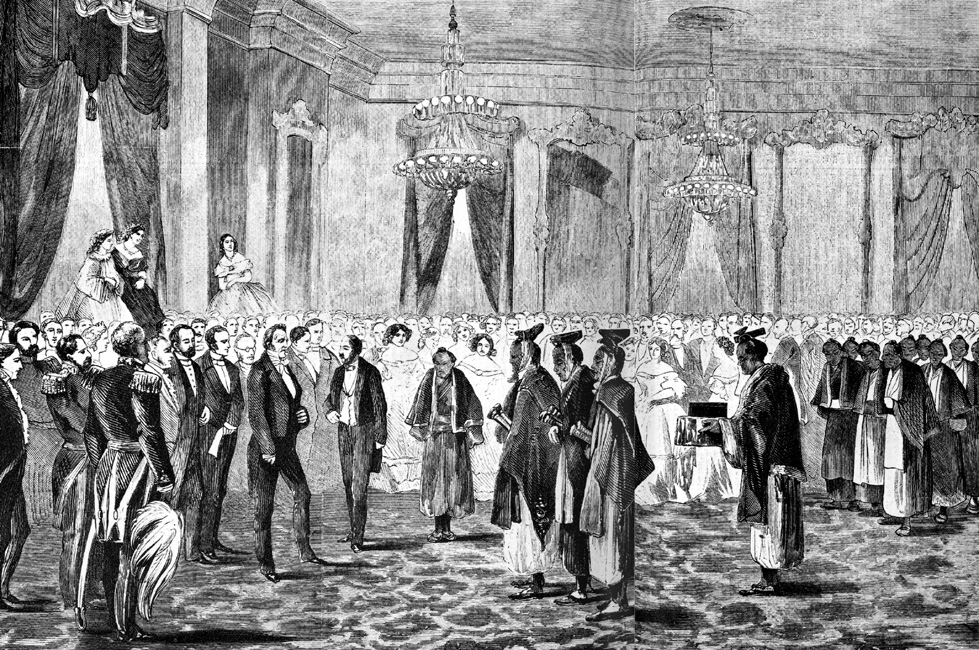

President Buchanan welcoming the Japanese Embassy, llustrated London News 1860(cf:Wikimedia Commons)

Photo by Akihide Saito

Photo by Akihide Saito

Naoe Kimura

Historian

Born in 1971 in Hiroshima, Kimura graduated from theUniversity of Tokyo, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Interdisciplinary Cultural Studies (completed the Ph.D. program). From 2000 she worked at Kyoto University of Art and Design as an associate lecturer. In 2003 she assumed a position of associate lecturer at Gakushuin Women’s College, Department of Intercultural Communication, and later became an associate professor at the same university. She specializes in cultural history and the modern history of Japan. Her major works include: “Seinen” no tanjo: Meiji Nihon ni okeru seijiteki jissen no tenkan” (Shin’yosha, 1998); “The Opening and the Being Opened” in “Modern Philosophy, Special Edition: Masao Maruyama” (Seidosha, August 2014 Issue); “ What People Saw When they First met Sociology: Contemplation on the First Steps of Social Sciences in Japan” in “Modern Philosophy, Special

Edition: The Ways and the Future of Sociology” (Seidosha,December 2014 Issue), and other works.